“In the Emperor’s Own Words” - Article by Sam Bernstein

Published by Chinese Art News Magazine, April 2001

The art of working jade achieved its most glorious age during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) and stands without comparison in the long history of China. Hongli, who ruled as the Qianlong Emperor, reigned from 1736 to 1795. He deliberately chose not to exceed the time span of the reign of his grandfather, the Kangxi Emperor. The Qianlong Emperor’s impact and importance to the Chinese monarchy is comparable to that of Queen Victoria’s importance to the British royalty.

Throughout the course of his life, the Qianlong Emperor was a grand patron of the cultural arts. The imperial collection at the time of Hongli’s death in 1799 contained more than one million items. As such, with the resources of the treasury and the imperial bureaucracy to draw upon, he exerted dramatic influence on the design, style and marketplace for jade works of art. The Qianlong style, as expressed in the arts, is remarkably recognizable and consistent; daring new forms were combines with a respect for antiquity.

This article examines five surviving examples of jade works that were previously in the Imperial Collection. All but one are distinguished by inscriptions executed in an adopted and descriptive style of palace court calligraphy. These inscriptions were added to each piece as a thoughtful observation and commentary at the order of Hongli himself. His words, as we shall see, provide a valuable insight into the mind of the man who as Emperor, was one of the greatest art aficionados in history.

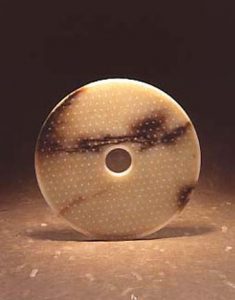

The Warring States bi disc illustrated in Figure 1 bears a poetic inscription composed by the Qianlong Emperor in 1789, which suggests a profound reverence for ancient works of art. By requesting that this impressive example be inscribed with his own poetic reflection, Hongli effectively marries the past and present, expressing his love of ancient forms with his own poetic ability. The poem, as recorded in the Imperial Archive reads:

Ah, the substance of the earth, I love your generosity of spirit

Bi, carved with ten thousand grains and extensive sentiment,

How well you serve as the emblem of the luminous court

Of which family’s cemetery were you the deep treasure?

The proportion of disc joined to hole is well done,

Like clouds caging the moon, but not obstructing its glow.

And the glow, from this concealment, does not make a garish display.

I hold in a sigh, thinking of what is ancient, yet still noble-minded.

Figure 1

In praising its form, workmanship and emblematic qualities, it becomes apparent from the poem that Hongli admires the ancient age of the disc and the refined “noble-minded” culture that produced it. It is this sentiment which is at the center of the concept of the literati or gentleman scholar’s pursuit of artistic refinement and connoisseurship.

The jade material of this bi disc is of a transparent yellow-gray coloration with rich streaks of dark brown running through it. The face of the piece is covered with an ordered array of raised modeled spirals which are enhanced with incised lines. This pattern is referred to as the sprouting grain pattern, which was developed in the Eastern Zhou period. According to Geoffrey Wills, author of Jade of the East, the grain pattern found on bi discs is thought of as “formal representations of neatly arranged rows of seeds. The curled variety is presumed to show the seeds sprouting through the earth, and thus to symbolize fertility.” According to Cheng Chia-hua of the National Palace Museum, one theory holds that the precursor to the bi disc was “a kind of stone spinning-wheel or (symbolic) jade millstone . . . . Such an agricultural origin is more strongly hinted at in the gu-bi (grain pattern disc) with its grain pattern décor.” The outer edge of the disc and the center perforation are framed by a flat, thin and raised border. The overall polish of the piece is smooth and matte, with some surface alteration which is evidence of prolonged burial.

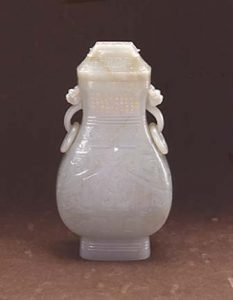

Figure 2

True to the heritage and distinction of a gentleman scholar, Hongli practiced the arts of calligraphy, poetry and painting. The emperor was a connoisseur and truly appreciated the great artists and works of the past. His artistic talents were cultivated with reverence and enthusiasm. Hongli was particularly fascinated with the medium of jade, and it inspired him to write many impassioned poems. The large (26.35 cm), covered archaistic vase illustrated in Figure 2 is one such example. This case is one of the few imperial jades that may be traced from its humble beginning as a tribute-gift of a raw boulder in the eighteenth century to the present day. It has passed from the Imperial Collection of the Summer Palace to the Prentice, Lady Yule, Spink & Son, Ltd., S.M. Spalding and Salman collections during the past two centuries.

The verse worked onto this piece begins with a reverential line directed toward a jade boulder the Emperor received as tribute from the Khotan region. The Chinese conquest of Xinjiang in 1790 opened up relations between the far western region and China, and allowed for an exchange of ideas which would influence the art of both cultures. The poem continues with the Emperor’s determination to study the classics:

A much treasured tribute from Khotan

Its form copied from the Bogutu (Illustrated Catalog of Collected Antiquities)

With pierced connecting rings on its sides

And a body covered with dense patterns.

One must be diligent in reading the Xiaoya (Discourse on Ordinary Refinement)

With proper lessons for instructing a gentleman.

During my travels I ponder over it again and again

Each time, shamed and inspired by its words.

The Qianlong Emeror, Spring of Yiwei (1775)

The vase has strong archaistic references, namely in the shape. Archaistic jades drew inspiration most heavily from the Bronze Age, which began around the sixteenth century, B.C. Bronze forms and decorative motifs of the Zhou period (1100-220B.C.) were of particular interest to many jade artists, as this was one of the most prolific bronze producing periods. The form of this vase is derived from an ancient hu vessel, a ritualistic wine container, and it also possesses pendant rings first seen in archaistic bronzes. This vase is documented in the year 1776 in Qing Gaozong Yuzhi Shiwen Quanji (A Complete Collection of Documented Literary Writings and Poems for the Personal Use of the Gaozong Emperor, i.e. The Qianlong Emperor), and is an excellent example of the superior jades once held in the Emperor’s personal collection.

The tradition of archaisms and archaistic styles in art began in the Song Dynasty (960-1279), and continued into later centuries, becoming particularly strong during the art of the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912). The poem makes reference to the Bogutu, a Song text that cataloged bronzes from imperial and other important collections. Because artists and scholars rarely had access to original archaic pieces, catalogs such as the Bogutu were essential references. Rather than merely imitate or copy the style of an earlier period, the jade artist most often attempted to create an archaistic work utilizing forms, styles, and motifs from the past to express a contemporary artistic ideal. In this piece, for example, both the fret pattern which marks the meeting of the cover and body of the vase, as well as the stylized dragon design which adorns its lower and upper sections are inspired by Shang and Zhou bronze motifs.

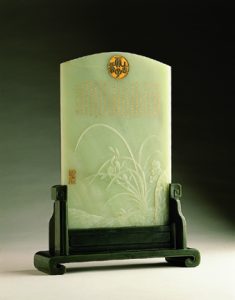

The magnificent imperial white jade screen pictured in Figure 3 embodies the artistic and scholarly work of several centuries. In incorporating various poetic texts with calligraphy and images from the Qianlong Emperor’s own hand (1711-1799), the work stands as a monument to achievements of previous scholars and the refinement of the emperor.

Figure 3

In 1754, the Qianlong Emperor made a calligraphic copy of a scroll by Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322), a famous Yuan painter and calligrapher. Thirty years later, in 1784, this work of calligraphy was incorporated onto the screen and marked with the large, circular, imperial seal.

The Emperor was very much inspired by Zhao Mengfu’s calligraphy and a poem by Su Dongpo (1037-1101) was inscribed onto this screen utilizing Su’s calligraphic style. The inscription in running script on the front of the this screen narrates the succession of the poem from the eleventh century to the eighteenth century and serves as an introduction to the piece.

Also inscribed on the screen is Dong Qichang’s (1555-1636) notation from the end of Zhao Mengfu’s scroll. The commentary dates back to the seventeenth century when Dong Qichang wrote that the scroll should be considered a masterpiece.

The inscription on the front ends with, “Summer of the Year Jiaxu (1754),” with imperial copy, and a small Qianlong seal. In ordering that the text be done in the emperor’s own calligraphic rendition and marked with the imperial seal, the Qianlong Emperor established himself both as a scholar and one who was able to appreciate the work of talented poets and calligraphers. In this way, he places himself in the tradition of scholars who, like Dong Qichang, eulogize the work of earlier intellectuals.

The calligraphy and seals are adorned with the original eighteenth century gold that has naturally altered with age. The reddish tone may be due to the presence of copper or lacquer in the gold itself. Fine relief below the calligraphy depicts blooming orchids with elegant leaves that bend in the breeze while a fantastic rock stands in the foreground. The softly polished screen is a semi-translucent, greenish-white coloration with subtle, darker inclusions. The piece is fitted with an original jade stand of a contrasting, spinach green coloration.

The reverse has two seals of the Qianlong Emperor, one circular and one square. A calligraphic piece by courtier Zhang Zhao (1691-1745) is incorporated onto the screen and inscribed with this commentary by the Emperor:

Fine jade from (Khotan) is made into this screen;

I also painted the lonely orchid on it, and fragrance fills the air.

My imitation of Zhao’s calligraphy that I have saved is now used for inscription.

Reading Su’s poetry is even better than sharpening (one’s mind) with a whetstone.

In this old age I do not write small characters anymore;

Remembering old times, (I had) the Waijing text carved instead.

Thirty years disappeared in the twinkling of an eye.

How can (my) calligraphy stand up to comparison?

For the inscription on this jade screen with a lonely orchid, I ordered the carving of my calligraphic copy of Mengfu’s calligraphy of a poem by Su Dongpo (Su Shi), which I did in the Year Jiaxu (1754), and the Huangting waijing jing poem as written by Zhang Zhao to commemorate this event.

The text for Zhang Zhao’s calligraphy is the famous Daoist text on the preservation of one’s health and is followed by, the Huangting text, humbly copied by courtier Zhang Zhao, together with Zhang Zhao’s seal.

The Qianlong Emperor had considerable training in calligraphy and a strong interest in collecting both old and new paintings. In 1744, he commissioned the first catalogs of ancient and modern calligraphies and paintings in the imperial collection (Shichu baoji). Cataloging was placed under the supervision of Zhang Zhao, but the Qianlong Emperor took a personal interest in the process. Inspired by his participation in the review of the palace collection, the Emperor began to enthusiastically pursue painting in the manner of the ancients. Song compositions of birds and flowers or Yuan paintings of dry tree and rock or bamboo compositions served as an inspiration for him. It is likely that one reason for the Emperor’s compelling urge to paint stemmed from his desire to be documented as an emperor-artist. By emulating the works of Song or Yuan artists, the emperor continued the tradition of classical painting and demonstrated his ability in another pursuit of the gentleman scholar.

This scholar’s screen is documented in Qing Gaozong Yuzhi Shiwen Quanji (A Complete Collection of Documented Literary Writings and Poems for the Personal Use of the Gaozong Emperor, i.e. The Qianlong Emperor), and is an excellent example of the superior jades once held in the Emperor’s personal collection. The integration of jades, painting, and calligraphy stands testimony to the emperor’s personal artistic passion.

Figure 4

The powerfully rendered jade seal, Figure 4, of Sanxitang, or Hall of Three Rarities within the Forbidden City, dated 1745, underscores Hongli’s commitment to collecting and treasuring works of art.

This authentication seal is an official seal of the Sanxitang, the Hall of Three Rarities. This hall is located inside the Forbidden Palace within the Hall of Mental Cultivation and so named because it was where Hongli originally kept the manuscripts of three famous fourth century calligraphers, Wang Xizhi, Wang Xianzhi, and Wang Xun. The following excerpt is from Wan Go Weng and Yang Boda’s The Palace Museum Peking: Treasures of the Forbidden City:

The west wing of the Hall of Cultivating Mind consists of several small rooms, partitioned during the Qianlong reign to suit the emperor’s taste and comfort. This section, completely shielded by an outer screen, was the most protected core in the entire City. A miniature hall within a hall, its own throne room is hung with imperial mottos in many forms. A horizontal tablet with four characters admonishes, “Be diligent in state affairs and close to the able and worthy.”

A vertical couplet reminds the ruler, “Though one person rules the world, the world provides not only for one.” The central rectangular frame contains a long poem composed and written by the prolific Qianlong poet-calligrapher-emperor himself, listing ten Confucian precepts for the monarch. Unfortunately, these high-minded sentiments, more often than not, remained mere decoration.

The Qianlong Emperor enjoyed a sixty-year reign at the peak of Qing dynasty’s peace and prosperity. During that time, he initiated large-scale construction both inside and outside the Forbidden City. However, the place that really gave Hongli endless pleasure was a small den at the southwest corner of this hall, an inner sanctum within the inner sanctum of the city. This is the famous Room of the Three Rarities, also known as the Hall of Three Rarities, so named for three rare pieces of ancient calligraphy, the last of which he acquired for his collection in 1746. Including the entrance area, the corner den affords a space only about 86 square feet in all. The silk painting on the right wall near the entrance, a joint effort of the Italian Jesuit painter Castiglione (known as Lang Xining) and his Chinese colleague Jin Tingbiao, done in the Western trompe l’oeil style, creates an illusion of depth by extending the interior tiled floor and ceiling woodwork into the picture.

Here, Hongli, after laboring over his “ten thousand cares,” would plunge into his fondest hobbies of connoisseurship, painting, calligraphy, and poetry, defacing selected painting and calligraphy from his vast collection with encomiums in mediocre verses of his own composing, inscribed in highly polished but ordinary handwriting. Extremely proud of his literary and artistic accomplishments, the emperor personally wrote the name of this room on the horizontal tablet and added a couplet under it: “Observing the ancient and the modern with all-encompassing attitude; relying on brush and paper to express the deepest thoughts.”

Calligraphy, which is devoid of pictorial content, is capable of sheer abstract beauty; taken together with the textual content, it can express and evoke intense feelings. Boyuan tie, or Letter to Boyuan by Wang Xun (350-401) is an extremely rare authenticated calligraphy by a master of the Jin period. When Hongli acquired this treasure in

1746, the Qianlong emperor named his favorite small den in the Hall of Cultivating Mind Sanxitang, or the Room of Three Rarities. The other two rarities, already in his possession, were a letter by Wang Xizhi (321-379) called Kuai xue shi qing tie, or Timely Clearing After Snow, and a letter Wang’s seventh son, Wang Xianzhi (344-388), called Zhong qiu tie, or Mid-Autumn Letter. Unlike the Letter to Boyuan, these two works are not in the calligraphy of their authors, but are later copies.

The beauty of Wang Xun’s letter so elated the emperor that a year after naming his inner sanctum he launched the monumental project of printing all the choicest calligraphy in the imperial collection. More than 340 pieces by 135 major calligraphers from the third to the seventeenth century are included in this collection, which is entitled Sanxitang fa tie (Calligraphic Masterpieces from the Room of Three Rarities). The best printing technique available in eighteenth century China for such undertakings was the painstaking method of ink rubbing from stone engravings. This involved tracing the original in ink onto paper soaked in oil and thoroughly dried to make it translucent. The tracing was then reproduced on the back of the paper in cinnabar ink and the cinnabar tracing transferred onto a finely polished stone following the cinnabar tracings; next, paper was laid over the stone, dampened, and pressed carefully into the engraved lines. Finally, ink was patted over the surface of the paper but did not reach the paper pressed into the intaglio-carved characters, which appear white against black on the printed sheet.

As the number of craftsmen skilled enough to do such work was very limited, it took six years to complete the collection. Although there are some imperfections – such as the inclusion of calligraphies of doubtful authenticity, as well as an occasional respacing of characters that marred the original compositions – the reproductions preserve in amazing fidelity many precious items from the Qianlong emperor’s collection that have since been lost or destroyed.

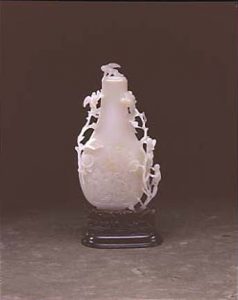

The fifth and final jade work of art which we shall examine is not inscribed, however the unusual subject matter and historical context provide a backdrop for understanding the cross cultural influence expressed in the art and architecture of China which Hongli encouraged and patronized. The highly unusual jade vase shown in Figure 5 suggests a strong European influence at the Imperial Court. The winged cherubs known as “miraculous messengers of momentous news” may possibly be a reference to Jesuit court artists who introduced religious subject matter in subtle ways on non-secular works of art at court. This was a conscious attempt to blend religious elements with the perceived taste of the court to bring attention to Western religious thought. Also, the shape of the acanthus leaf shown on this vase is of European origin and of a type not seen on Chinese jade works of art prior to the Qing dynasty.

Figure 5

The Jesuit priest Giuseppe Castiglione was presented at court in 1715. As an artist and architect, he was instrumental in the introduction and development of Western design in China. His Italian design of the western façade of the Palace of the Calm Sea brought classical Western concepts of design to Chinese artists. A well-known piece created by this artist during his stay in China depicts European-style cherubs (putti in Italian) very similar to those seen on this vase. Castiglione was also responsible for the overall botanical style present in the Yuanmingyuan (Summer Palace), the Chinese version of Versailles.

This vase was formerly in the collection of Bluett and Son, London, in 1940, and then entered the F.N. Volkert collection in Chicago. During Mr. Volkert’s lifetime, it was exhibited in The Mint Museum in Charlotte, North Carolina. It later entered the J.M. Holland collection in California. It is appropriate that this historical vase now resides in a collection in Asia.

That Hongli, the Qianlong Emperor, was an ardent collector of art as well as a connoisseur is beyond question. It is through an examination of his calligraphic work applied to jade works of art that we glimpse his real love for antiquity and excellence in the arts of China. It is fitting that these remarkable objects have survived during the past two centuries and are studied and enjoyed to this day.

Sam Bernstein

For further reading:

Qing Gaozong Yuzhi Shiwen Quanji (A Complete Collection of Documented Literary Writings and Poems of the Qianlong Emperor). Taipei: National Palace Museum, 1976. Volume 7.

Zhongguo Meishu Fenlei Quanji: Zhongguo Yuqi Quanji 6, Qing (Chinese Art Series: Chinese Jades, Volume 6, Qing). Li Jiufeng, ed. Shijiazhuang: Hebei Art Publishing, 1991.

Ming Qing Dihou Baoxi (Precious Seals of the Emperors and Empresses of the Ming and Qing Dynasties). Beijing: Palace Museum, 1996.

The Refined Taste of the Emperor: Special Exhibition of Archaic and Pictorial Jades of the Ch’ing Court. Chang Li-tuan. Taipei: The National Palace Museum, 1997.

The Palace Museum Peking: Treasures of the Forbidden City. Wan Go Weng and Yang Boda. New York: Henry N. Adams, Inc., 1982.

Hello. I have a circular mint colored jade disc-about 8X8” that I was told came from the Qing Dynasty.It has been in our family since 1945, possibly acquired at an estate auction in Cle, Ohio. I would like to have it appraised. I am living in Fla. now. Can you assist me with who may be able to do an appraisal?